An article from JoongAngIlbo below. Pictures as well.

Kim Young Jin is easily spotted among the chattering elementary school students. Wearing a crisp T-shirt, the 11-year-old appeared no different from his classmates except that he was sitting alone while other children were gathering in groups of two or three.

“What kind of games do South Korean kids play?” asks Kim (not his real name). “Do they play FIFA [an online soccer game] like kids in China?”

Kim’s family came to South Korea from Hambuk in the North by passing through China, and he is attending a South Korean public school. However, adapting to a new and unfamiliar environment has not been easy.

“It’s just that he is little bit different from the other kids that makes him feel like an outcast,” says Kim’s mother. “I’m worried he won’t fit in.”

Kim and others like him face two primary hurdles, according to Park Da Som, 27, a social worker at Dongbu Hana Center in Bundang, Chungsol Village, an organization that works to help North Korean defectors adapt to life in the South.

“First, it’s the language,” she says. “We thought children would be capable of adjusting quickly to the South Korean language, unlike the adults. However, they also seem to have a hard time.”

The other obstacle is not so straightforward. “The second problem is the immense gap in children’s experience,” says Park. “It is the center’s job to assist North Korean children by organizing our program into three sections: mind-up, dream-up and brain-up.”

Mind-up provides opportunities for North Koreans to experience the culture of the South by visiting amusement parks, theaters and other places that are part of children’s lives.

Dream-up utilizes psychological and career monitoring for five years and introduces students to a wide range of occupational possibilities by visiting schools, factories, farms, bakeries and office workplaces.

The brain-up program gives one-to-one mentoring by enlisting some of the top high school students in South Korea. It also supplies workbooks and college application information to support students who aspire to continue their education.

“I was able to keep up with schoolwork through the mentoring program since my mentor showed me how to study after considering my actual learning capacity,” says Lee Jee Seon, 11 (not her real name).

And the benefits of the brain-up program don’t stop with the students. “The mentoring system allowed me to grasp educational trends of Korea and let me know how to help educate my daughter,” says Lee’s mother. “Also, the mentor helped my daughter gain confidence and I could see her improvement.”

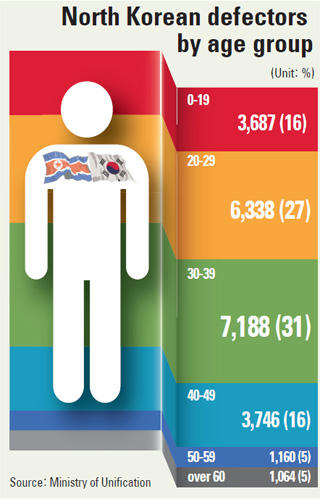

With the number of young defectors on the rise in recent years, the work of organizations like the Dongbu Hana Center is more important than ever.

“The percentage of young adolescent North Korean defectors is increasing as years pass,” says Park. “Teenagers are very sensitive to friend relationships and unaware of own self-identities, so they are vulnerable to negative influences during the harsh process of defecting and settling down in a completely new world. There are even incidents where children are mistaken as ‘problem children’ because others fail to understand the stress they are facing.”

“I hope people can understand the delicacy of these juvenile defectors.” Assisting in the assimilation of these young defectors is the responsibility of the community.

“The center lacks volunteers to teach English, yet most of the children find English the most difficult subject to study,” says Park.

Those interested in the English assistance program are welcome to visit the Chungsol Multicultural Family Welfare Center or call (031)714-0125 for more information.

By Lee Haa-kyung and Yoon Eun-kyung